Has all of human history already been digitized? AI and Google have created a real-life Borgesian Library of Babel, scarfing up millennia of literature like some mythological Kraken. Thanks to technology that can clone, photograph, or scan film and video, still photography, sound recordings, print media, paintings, sculptures, and architecture, many traditional functions of physical libraries are becoming obsolescent. Hundreds of thousands of phonograph records, originating from the late 19th century onward, have been digitally cleaned up and made publicly accessible, often on YouTube. The same is true of kinescopes of early TV and 70-year-old videotapes, as well as older newsreel films. The Theatre on Film and Tape Archive at the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center in New York has been preserving archival videotapes of Broadway, off-Broadway, and regional theater productions since 1970. More recently, advances in holography have even resurrected famous entertainers of the past as creepy but credibly lifelike digital avatars.

The permanent digital preservation of our cultural legacy therefore seems assured. Or is it? Has every nook and cranny of the mansion of art been rediscovered and captured?

Of course, not everything is available for digitization. There are the notorious lost works of history’s canon: most of the tragedies written by Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripides; the ancient library of Alexandria, destroyed by fires; Shakespeare’s lost plays Cardenio and Love’s Labour’s Won; the never recovered works of art looted by the Nazis; the Buddhas of Bamiyan statues, demolished by the Taliban in 2001; the original uncut versions of the films Greed and The Magnificent Ambersons. Some works designated for the trash bin were rescued against the wishes of their creators, like the writings of Franz Kafka, posthumously preserved by his friend Max Brod. Some lost artworks may be apocryphal, but many were verifiably real.

In the arena of American art, there is virtually no surviving film footage with audio that records live performances of the great actors of the era of the theater on Broadway before the mid-20th century—an era of the stage that was unique and uniquely different from today’s theater. Because our sense of cultural memory has become so visual in our post-print era, written reminiscences and drama criticism have lost much of their previous authority to describe that past, and without visuals (think Ken Burns), the public’s sense of our theater heritage increasingly disappears. Thus there is a giant bomb crater in collective memory—what critic Clive James termed cultural amnesia—where images of the heyday of American legitimate theater before television ought to be securely lodged, but aren’t.

Movie stars of the Hollywood studio era still play to thousands on TV’s Turner Classic Movies. But many well-educated people don’t know anything about the leading stage players of that same era: Alfred Lunt and his wife, Lynn Fontanne; Noël Coward and his stage partner, Gertrude Lawrence; Tallulah Bankhead; Michael Chekhov; John, Ethel, and Lionel Barrymore; Ruth Gordon; Pauline Lord; Walter Hampden; Katharine Cornell; Judith Anderson; Maurice Evans; Ina Claire; John Gielgud; June Walker; Eva Le Gallienne; Helen Hayes; Florence Reed; Florence Eldridge (who usually appeared with her husband, Fredric March); Helen Gahagan (who married Melvyn Douglas and became a politician); Alla Nazimova; and Laurette Taylor, among others. With the exceptions of Coward and Lawrence, all these performers appeared only in plays, never in musicals. Forgotten also are the stage comedians of that era, like Bobby Clark, Fanny Brice, Bert Lahr, Eddie Cantor, Ed Wynn, and Beatrice Lillie, though they appeared in a few films, and the incomparable monologuists Ruth Draper (who made no films) and Cornelia Otis Skinner (who appeared only in three). These American stage luminaries have disappeared as completely as have their 19th-century predecessors Edwin Booth, Edwin Forrest, Minnie Maddern Fiske, and Joseph Jefferson.

Live theater is ephemeral by its very nature; archival videos of stage performances, though good to have, only sketchily represent the enveloping depth of the experience of seeing a play in person. A goodly number of ballets and modern dances, as well as famous dancers of the past, were also never captured on film, though much classic choreography is preserved through labanotation or other reconstruction methods. But except for mime, the art of live theater performance relies on the all-important element of speech, which doesn’t exist in dance.

The American iconography of apple pie, log cabins, Sousa marches, ragtime, jazz, vaudeville, Beat poets, slapstick comedy, the Great American Novel, Mark Twain, the Oscars, Elvis, Old Blue Eyes, Babe Ruth, and other cultural totems is bereft of any images of the once iconic Barrymores. John, Lionel, and Ethel Barrymore were household names before 1950, but how many young people who watch Drew Barrymore on TV today know the lineage of her famous surname? Yet the play The Royal Family, a thinly veiled account of the Barrymores, was a huge hit on Broadway in the 1920s, and nobody had to be told to whom the title referred. Today the phrase “the royal family” conjures what remains of the House of Windsor in Britain, or perhaps the Logan Roy family on Succession. There is no royal family of the theater in 21st-century America, as there was with the Barrymores until about 1960, or the Booths in the 19th century.

The theater had a star system in those days, with the biggest names usually de facto producing and directing their own star vehicles even if others were credited on the playbill with those tasks. Actors like Katharine Cornell and the Lunts were national celebrities, known well beyond New York City, because they took all their Broadway productions on long national tours. They also performed in abridged re-creations of their plays for the widely listened-to program of old-time radio, Theater Guild on the Air. They were celebrated like rock stars in the popular 1943 film Stage Door Canteen, a patriotic wartime potboiler in which several of them made cameo appearances serving GIs cafeteria-style food. (The Stage Door Canteen was an actual place on West 44th Street in the theater district during the war, where entertainers were expected to volunteer as busboys or food servers.) They were paid homage in popular movies about the Broadway theater in the 1940s and ’50s, like the multiple Academy Award–winning All About Eve and A Double Life, which featured Ronald Colman as an actor who gets so absorbed in playing Othello that it carries over into his real life. (Colman won an Oscar for the performance.)

Except for the Barrymores, few stage stars who emerged in the 1910s and 1920s appeared in more than a smattering of movies; some, like Katharine Cornell, never made a movie at all. The Lunts made only one, and Laurette Taylor appeared only in silent films. To be a theater star in that past era was glamorous in itself and did not need the added tinsel of motion picture stardom. Laurette Taylor’s performance as Amanda Wingfield in the original 1945 Broadway production of Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie was almost universally remembered even 50 years later, by theater professionals who had seen her, as still the greatest acting performance they had ever seen. No subsequent actress playing Amanda Wingfield has ever dislodged Taylor’s reputation in the role, whereas many actors have challenged John Barrymore’s legendary 1922 Hamlet for supremacy.

John Barrymore, astounding in some of his silent films, is a disappointment in most of his sound films. Except in Counsellor at Law (or possibly Topaze, or as Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet—opinions differ), he generally walks through his most famous roles with uninvolved, glib readings, often giving self-parodying performances. In one electrifying moment, though, in Playmates, a largely forgotten 1941 film starring the bandleader Kay Kyser, the booze-dissipated Barrymore suddenly starts intensely reciting Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” speech only to go up on his lines. In a 1977 television interview, the venerable actress-director Eva Le Gallienne, who had seen Barrymore onstage many times and knew him personally as Jack, recalled that Barrymore hated the phonograph and radio recitations of Shakespeare he had recorded, and that they were exaggerated and not representative of his actual stage performances. The aging Le Gallienne, who was then appearing in a few movie and TV roles, added that she still thought John Barrymore was the greatest actor America had produced in the 20th century.

What was so great and different about these older actors onstage? Take Michael Chekhov, a nephew of Anton Chekhov, little remembered now save for a few small film roles, notably as Ingrid Bergman’s psychiatrist mentor in the 1945 Alfred Hitchcock film Spellbound. As the stage director and drama critic Harold Clurman wrote, “Chekhov is one of the few great actors of our time. … What he does in pictures hardly represents even the surface of his talents. (Playing a Russian repertory, he gave us a series of magnificent stage portrayals in a season that passed practically unnoticed on Broadway in 1935.) His film performances—including the one in Spellbound—are not true samples of his art.” Chekhov was the legitimate stage’s answer to Lon Chaney, a kind of pre-method actor who was also an incredible master of 1,000 disguises, stage makeup, and costumes. Reviewing the eight-play repertory at the Majestic Theater in which Chekhov created multiple characters in 1935, the New York Times critic Brooks Atkinson wrote, “Their wigs are hideously extravagant. Mr. Chekhov is amazingly versatile. To impersonate an absent-minded shopper, he is made up like a bald-headed curmudgeon encumbered with innumerable packages, with flaring whiskers that set the audience to itching.” Who onstage today would have the technical craft to change his makeup and costumes so many times so quickly within the same performance, and at the same time to bring emotional truth to such a diversity of over-the-top roles?

Almost a century has passed since Michael Chekhov’s heyday, when the work that actors did onstage could be more powerful than what they did on film. Instead the theater has become a medium for celebrity TV and film actors, who may or may not have a strong background in live theater, to draw audiences and guarantee the box office. The late Aaron Frankel, who had worked as a stage manager for the Lunts and later became an acting teacher and director, years ago told me, “I saw Laurence Olivier in The Entertainer both on Broadway and later in the movie. Here was a first-rate actor portraying a fourth-rate performer, and it worked. The Entertainer was the best theater I’ve ever seen. Believe me, Olivier’s live performance was even better than his movie performance.”

Frankel was one of many with long memories. As recently as the late 1990s, there was still a backstage fraternity in New York of actors and production people who remembered what the old-time performers had been like 60, 70, even 80 years before. Almost all were elderly, some pushing 100. I met many of them. They were like craggy, wizened veterans of Pearl Harbor or D-Day who vividly remembered the scenes of battle, or ancient baseball players recalling their youthful playing days with Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner. Undoubtedly they are all gone now.

I visited the theater’s greatest caricaturist, Al Hirschfeld, in 1998 and asked him what made the old-time stage actors different. He had seen, and caricatured, John Barrymore onstage way back in the 1920s. As he sat drawing in his famous barbershop chair at age 95, on the top floor of his townhouse in the East 90s, he told me, “The actors onstage today are smaller and more realistic than the old-time actors. The actors on stage are not bigger than life, they’re smaller—they’re a part of life now. I think the Actors Studio had a profound influence on that. That’s why in the early days of movies, all the great stars in the theater—the Lunts, Katharine Cornell, and so on—they never made it in movies. They were just too big. Their movements were too large. Just overblown. They were like exploded ventricles. They were really broadcasting without an instrument.”

Some of the great theater performers of that day—Helen Hayes, Ruth Gordon, and Florence Reed—were small, mousy women and not great beauties, and were not expected to be. Their mystique resided in what illusions they created for the audience. They were powerhouses onstage. As the Broadway producer Morton Gottlieb, who started as a theater press agent in the 1940s, told me, “Stars like Gertrude, their larger-than-life-ness didn’t quite fit in on screen, because in movies, you’re not supposed to be over-dimensional. But television has changed all that.” Perhaps the supreme exemplar of this larger-than-life quality was Katharine Cornell, who, together with her husband and director, Guthrie McClintic, was the producer of her own Broadway productions and their national tours. She was best known for roles in The Barretts of Wimpole Street, in various classical and restoration plays, and in Chekhov, Shaw, and Shakespeare. Though unprepossessing in real life, she radiated a unique charisma on stage. “Something psychological happened when she made an entrance. Audiences could not be indifferent to her presence,” wrote Brooks Atkinson (of The New York Times). Harold Clurman wrote that Cornell’s “enigmatic mask, mysterious voice and suave movement had about them something luxuriously and old-fashionedly theatrical, brooding, chic, and up-to-date all at the same time. … Onstage she seems always to be visiting the twentieth century from another realm.”

People I spoke with who had seen her told me much the same thing. Peter Harris, an actor who had appeared with Helen Hayes and Ethel Barrymore in the early 1940s, said of Cornell, “There was nothing fluttery or stage-center-y about her, yet you didn’t take your eyes off of her. She was a strangely large woman on stage.” I once had a phone conversation with the legendary theater historian Gerald Bordman, who had seen everybody and everything in the old days. I casually mentioned Cornell, and he cut me off with a whisper: “Ohhhhhh—she was my favorite actress.” Cornell was also George Bernard Shaw’s favorite American actress (she appeared on Broadway in his plays Candida and Saint Joan); he wrote to her in the 1930s, “If you look like that it doesn’t matter a rap if you can act or not.” Cornell’s company gave very early acting opportunities to the teenage Orson Welles and the young, unknown Marlon Brando. It was commonly held that there were three “first ladies” of the theater in those years: Katharine Cornell, Helen Hayes, and Lynn Fontanne.

Katharine Cornell in the 1931 stage production of The Barretts of Wimpole Street (Vandamm Studio photograph/Wikimedia Commons)

George Drew, an actor and costume designer who was a cousin of the Barrymores, told me, “Laurette Taylor’s telephone conversation when she’s selling subscriptions in The Glass Menagerie was probably one of the greatest moments I’ve ever seen in the theater. I’ve seen the play at least four or five times since, and nobody has ever made me see all the other people on the other end of the line the way Laurette Taylor did. Now don’t ask me what she did. I knew exactly who that person was she was talking to. It was that kind of magic. That was something that she did and nobody else has ever been able to do.”

Ruth Draper, the great monologuist (or diseuse), could make Broadway audiences believe in an entire invisible cast of characters despite her being a one-woman show. Howard Whitfield, a veteran Broadway production stage manager whose theatergoing began back in the 1930s, told me, “Ruth Draper spoke several languages in her shows. One scene I remember, because it was so touching, was called ‘The Flag.’ She played the whole thing in French. Draper played this woman with a shawl around her head carrying a baby in her arms who was watching a group of soldiers come home. She talked to them in French, and you knew what she was saying even if you didn’t speak French. But she would talk to first one, and then to another, and finally, she got the word that her husband had been killed. And so she was crushed—but then suddenly she saw the flag being carried, and she took her baby’s hand and said, ‘Le drapeau! Le drapeau!’ and marched off the stage following the flag.

“Other times she interspersed English with Italian. She performed a piece called ‘Court of Human Relations’ where she played three generations, and one of them spoke no English, another one spoke some English, but the whole story was told, and even if you did not understand the language, you knew what the story was because she herself became this person. Whatever she was saying, you understood the meaning.” Ironically, Draper left this mortal coil in a theatrical situation: She succumbed to a sudden heart attack in December 1956, only hours after giving a performance at the Playhouse Theater on West 48th Street, forcing the producers to cancel the remaining performances of the run.

Whitfield remembered many other performers. “I saw Laurette Taylor in the 1938 revival of Outward Bound playing Mrs. Midget. She was adorable, fragile, and heartbreaking. Ethel Barrymore in Whiteoaks was a very powerful actress on stage, too. Helen Hayes I remember in Dear Brutus: that heartbreaking end of the second act, where she says, ‘Daddy, Daddy, come back!’ I also saw Maurice Evans and John Gielgud in their respective Hamlets in the 1930s. Evans was a more believable person. Evans was more down to earth. Gielgud grew up after that Hamlet. He was a very young actor. I also saw Maurice Evans in Richard II, and in that he was very inclined to ‘sing.’ I do not feel he did it so much in Hamlet.”

The married Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne were legendary for their almost monastic devotion to preparing their performances down to the most intricate detail, so that when they interrupted each other’s dialogue on stage (“biting your cues” in stage parlance), it seemed naturalistic and spontaneous. Their only film, The Guardsman (1931), based on the Ferenc Molnar play that they had performed on Broadway in 1924, is a permanent document of their infinitely detailed nuances of timing, subtle sexiness, and magical ability to manipulate your belief with masklike ambiguities of behavior. In the Lunts’ production of O Mistress Mine in 1946, George Drew briefly understudied Dick van Patten as the teenage son of Lynn Fontanne. He told me, “I used to watch Ms. Fontanne go onstage before the curtain went up as I was standing in the wings. She had this gown on with all ruffles starting at the neck, ruffled all the way down to the train. With the curtain still down, she entered the stage, sat on the sofa, and started moving her index finger from the toes up to dishevel the arrangement of the ruffles, so that when the curtain went up, she would look like she’d plopped herself down on the sofa and mussed up her gown. The curtain goes up, she’s stretched out on the chaise, the phone goes off, she reaches over, picks it and says, ‘Olivia Brown here.’”

Frances Tannehill, who had been a child actor in the 1930s, told me, “I saw Alfred Lunt in the play Quadrille, and he had one speech where he described a train ride, of all things, and as he spoke, his voice actually fell into the rhythm of the train as if he were on it. It was a tour-de-force. It stopped the show cold.”

In Chapter 17 of J. D. Salinger’s novel The Catcher in the Rye, Holden Caulfield takes his girlfriend Sally Hayes to a Broadway matinee of the 1949 play S. M. Behrman play I Know My Love (the title is not mentioned):

The show wasn’t as bad as some I’ve seen. It was on the crappy side, though. It was about five hundred thousand years in the life of this one old couple. … Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne were very good, but I didn’t like them much. They were different, though, I’ll say that. They didn’t act like people and they didn’t act like actors. It’s hard to explain. They acted more like they knew they were celebrities and all. I mean they were good, but they were too good. When one of them got finished making a speech, the other one said something very fast right after it. It was supposed to be like people really talking and interrupting each other and all. The trouble was, it was too much like people talking and interrupting each other. … But anyway, they were the only ones in the show—the Lunts, I mean—that looked like they had any real brains. I have to admit it.

Even Harold Clurman wrote that he found the Lunts’ performance in I Know My Love “thoroughly irritating.” But he also wrote that Alfred Lunt was “the most gifted and accomplished player of the generation which followed John Barrymore … a player without peer on our stage.”

The last hurrah of these bygone performers was the Broadway season of 1957–58, arguably the greatest season on Broadway of the last 75 years. It was the last time that all of the “hall of famers” of yore (save John Gielgud) appeared “on the boards” in the same New York theater season. It marked the final appearance, and some say greatest performance, of Lunt and Fontanne, in a searing drama far removed from their typical drawing-room comedies, Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s The Visit. “It was a terrible tale of vengeance,” Frances Tannehill told me. “Watching it was like being pulled through a knothole.” Some patrons fainted during the intense final scene when Alfred Lunt, about to be murdered by a mob onstage, actually vomited at every performance. (One night, during the British production, a woman in the audience even died during that scene.) The same year, Laurence Olivier gave his epic performance as a failed vaudevillian in The Entertainer. Katharine Cornell made her second-to-last Broadway appearance as an Egyptian pharaoh’s sister in The Firstborn by Christopher Fry (she had played Cleopatra 10 years earlier in a famous production of Antony and Cleopatra). Helen Hayes appeared as the sibylline guide to Richard Burton’s fantasied past in Jean Anouilh’s play Time Remembered. Noël Coward appeared in two of his own magnificently witty plays, Nude With Violin and Present Laughter.

Film stars Henry Fonda, Ralph Bellamy, Anthony Perkins, and Tyrone Power also appeared on the boards in 1957–58, as did such celebrated actors as Julie Harris, Shirley Booth, Peter Ustinov, and Zero Mostel. Plays by Shaw, William Saroyan, Dylan Thomas, William Inge, and Carson McCullers all had decent runs, and Elia Kazan, Margaret Webster, Peter Brook, and Peter Hall were among the illustrious directors that season. In musicals, the season marked the debuts of West Side Story and The Music Man.

The week after West Side Story opened, the Soviet Union launched its Sputnik satellite and thereby ushered in the space race—and the beginning of the end of a golden age of theater. When Cornell’s director-producer-husband, Guthrie McClintic, died in 1961, she immediately retired from the stage.

II

Centenarians in any distinguished field are rare. A very few Hollywood movie stars have reached ages from 102 to 105: Luise Rainer, Olivia de Havilland, Marsha Hunt, Kirk Douglas. I know of only four veterans of the American stage who lived to celebrate a 106th or higher birthday. Doris Eaton, the last surviving Ziegfeld Follies girl from the 1920s, died at 106 in 2010. The urbane Norman Lloyd, known to old-movie buffs for falling from the Statue of Liberty in the final scene of Hitchcock’s 1942 suspense thriller Saboteur, and to more recent generations as Dr. Auschlander on TV’s St. Elsewhere, made it to 106 in 2021. George Abbott, the dean of Broadway directors, who began his career as an actor in 1913 and directed a Broadway revival of the musical On Your Toes in 1983 at age 95, lived to be 107. The fourth of this quartet—the least famous, but the only one of the four to live in three centuries—I had the privilege of meeting and interviewing when he was 102. Tonio Selwart, stage and film actor, born June 9, 1896 in Bavaria, died in New York City on November 2, 2002 at age 106. He was the closest thing to a human time machine, to a living panorama of the history of the theater, I ever met.

Tonio was a backstage legend in the theater community. He had lived for some 40 years in a spacious rent-controlled apartment at 130 West 57th Street, just a few paces east of Carnegie Hall. (For years before that, he had lived in an apartment around the corner on West 54th Street, opposite the now defunct Dorset Hotel, which he sublet to Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya in 1944 while he was away making films in Hollywood.) I was introduced to him by the aforementioned Frances Tannehill, whom I had befriended. She was the daughter of actor-director Frank Tannehill Jr., who had appeared on Broadway in the first decade of the 20th century; her paternal grandparents had appeared in plays around the time of the Civil War with Edwin Booth, John Wilkes Booth, Lillie Langtry, and Helena Modjeska.

In 1930, at age eight, Frances Tannehill had her Broadway debut in Purity with Florence Reed and went on to appear in many Broadway plays and musicals for decades, including a spell playing Bianca in the 1943 Margaret Webster production of Othello with Paul Robeson, José Ferrer, and Uta Hagen. “I’ve seen Moses Gunn and James Earl Jones in the role, and neither of them could hold a candle to Robeson,” she remembered. “He was magnificent. I was very much in awe. He had a dresser, Andy, a West Indian, and he used to have a split of champagne during the performance for his voice, just a little bitty thing, and Andy would sometimes give me the dregs.”

At 102, though blind from glaucoma, frail, and wearing hearing aids, Tonio Selwart lived independently. He came to the door himself (using crutches) when Frances and I rang the bell. He was dressed in natty, elegant clothing, a cravat around his neck. (His helper was not present either time I visited him.) Though his eyes were rheumy, he had a full head of white hair. If you closed your eyes and listened to him speak, you could have mistaken him for an urbane cosmopolite of 75. His memory was unimpaired. He had outlived his wife, Claire, a sculptor, by 60 years, and Ilse Jennings, his later companion, by 30. He talked warmly and without sadness about both of them, as if they were living presences still at his side. I later asked the building’s elevator operator how Tonio could possibly live by himself, blind, at 102 and often with no one else in the apartment. “Focus,” the elevator operator replied. “He keeps focused.” The second time I visited, I played Tonio a cassette tape recording of actors he had known from the legendary Group Theater of the 1930s. When his machine jammed and I tried to rewind it, I worried that I had upset his carefully managed tactile plot to find his objects sight unseen.

Tonio was so old, he had emigrated from Germany to the States before Hitler came to power. He was so old, he had been a lieutenant in the Austrian cavalry in World War I, had seen Emperor Franz Joseph (who died in 1916) in person, and had attended the first production of The Threepenny Opera in Berlin in the late 1920s. As I sat listening to him reminisce, I felt as if I were watching a real-life Jack Crabb—the fictional 121-year-old veteran of Custer’s last stand at Little Bighorn, portrayed by Dustin Hoffman in the 1970 movie Little Big Man—or perhaps Everett Sloane and Joseph Cotten in aging makeup reminiscing about the young Charles Foster Kane. Tonio had known Thomas Mann (and his children Erika and Klaus), Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo, Charlie Chaplin, Noël Coward, Gertrude Lawrence, Helen Hayes, Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, Conrad Veidt, Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya, Peter Lorre, Michael Strange (John Barrymore’s second wife), Diana Barrymore (Barrymore and Strange’s ill-fated daughter), Ethel Barrymore, the German playwright Frank Wedekind (who died in 1918), Orson Welles, Marlon Brando, director Max Reinhardt, and many more of the theater’s luminaries. In person, Tonio’s charm and sunny serenity made his frequent typecasting in Nazi roles seem improbable; like Conrad Veidt, he was an anti-Nazi who sometimes played Nazis. Fluent in French and Italian (he was of Italian descent on his mother’s side) as well as German, he had appeared acting in different languages in American, French, and Italian films, but never in a German one.

“It is different now,” he said. “At that time, there was a little bit of a star system: Alfred Lunt, Helen Hayes, Katharine Cornell, Alla Nazimova, and so on. People went quite a lot to see them. Is it still the same? No, it’s not the same.”

Tonio came to the United States in 1932 after establishing himself as an actor in the German and Swiss repertory theater; having lived for a period in Britain and already speaking English, he almost immediately began to work as an actor here. “When I came to this country, Carl Van Vechten [the writer and photographer] took my photograph and showed it to Eva Le Gallienne. She hired me, and I acted in her Civic Repertory Company productions for a whole year. She was a very intelligent woman, though I had the feeling, when she was playing, she was a little bit her own critic. She didn’t get completely into a part. But in later years, when I saw her on Broadway, I thought she was remarkably good.”

The great Russian actress Alla Nazimova appeared in Le Gallienne’s 1933 production of The Cherry Orchard. Tonio saw it. “There was a rather exotic quality about Nazimova, her speech sounded like a flute at times. It was miraculous how, when as Madame Ranevskaya she came home to Russia, she recreated the quality of a child when she saw her own room again. Then at the end, when the cherry orchard is sold, and you heard the slaughtering of the trees, the actor playing her brother, Paul Leyssac, put his hand on Nazimova’s shoulder. That was Le Gallienne’s direction. But offstage, Nazimova wasn’t happy with it. I overheard her say to Leyssac, ‘Paul, I didn’t act very much there, so you know what we’ll do? We’ll put our heads together like two forlorn horses.’ It was a brilliant suggestion! It made it so much more touching. That’s what I’m trying to say: Eva Le Gallienne was a very excellent actress, but there was something special about Alla Nazimova.” The playwright Gerhart Hauptmann called Nazimova the American Duse. In 1919, she purchased the Hayvenhurst estate in West Hollywood and later converted it into the Garden of Alla; this hotel for showbiz people was her eponymous home until she sold the place in 1930. (The new owners added an h to the name, turning it into the Garden of Allah.)

In 1933, the Theater Guild cast Tonio as the lead in The Pursuit of Happiness, a play about a Hessian mercenary fighting for the British in the Revolutionary War who falls in love with an American girl. It ran for a year on Broadway, cementing his reputation as an actor. About this time, “I became a very good friend of Lee Strasberg. I liked him very much. At that time, he lived on the West Side and was not too well off, and he had only four or five students. This was years before the Actors Studio was founded. He directed me in a summer theater play, Flight Into China, written by Pearl Buck. It didn’t come to New York. So many people were afraid of Lee! But I learned a lot from him. I knew Stella Adler quite well too, but she was not on good terms with Lee Strasberg. They didn’t like each other at all. Unfortunately, she wasn’t as good an actress as she was a teacher. She was not that great on stage. Neither was Strasberg. But I saw Elia Kazan before he became a director, as an actor in Clifford Odets’s play Golden Boy. His autobiography was read to me, and in it he wrote he thought he had too much energy on stage as an actor. But I didn’t think that at all when I saw him. He was a good actor, better than Strasberg or Adler.

“I did Maxwell Anderson’s play Candle in the Wind in 1941 with Helen Hayes. Alfred Lunt directed. I played Lieutenant Schoen, a Nazi who was trying to help Helen’s lover escape from a concentration camp. But the end of our big scene wasn’t working, and Alfred knew it. The playwright had written that my character said to Helen, ‘If I call you tonight, everything will be all right, but if I do not call you, there is no hope.’ But the line went flat with the audience, the curtain fell, and there was no applause. So Alfred and I added a curtain line for me: After Helen exited, I turned my back to the audience and screamed, ‘If I help this woman, the Nazis will kill me!’ That line got big applause as the curtain fell. Many years later, I was at a dinner party at [playwright] Paul Osborn’s, and Lynn Fontanne was there without Alfred. She came up to me and said, ‘Tonio, I remember you so well in Candle in the Wind. Tell me, how was Alfred as a director?’ It was very naughty, in a way, to ask me if he hadn’t been good. She was slyly joking. Actually, they were always directing themselves all the time.

“I admired Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, of course—but I thought perhaps sometimes they could have done a little bit too much. Strangely enough, I never had that feeling with Noël Coward and Gertrude Lawrence. It is difficult to answer this question, if someone is a little more labored or a little more natural. I would think that Gertrude Lawrence and Coward seemed even more relaxed than Lynn Fontanne and Alfred Lunt.

“But I think Laurette Taylor was one of the greatest actors we had. I spoke so much about Nazimova, but if I would compare, I would really prefer Laurette Taylor. They were very different in the sense of reality. Laurette Taylor had more reality. In Nazimova, you admired the wonderful technique, and the wonderful surprising reactions she would play, or a tone which touched you very strongly—there was a fascination about Alla Nazimova. With Laurette Taylor, there was not a fascination, it was that she just got you, she touched you very hard, very warmly. I met Ethel Barrymore, and I saw her on stage a little bit, not too much, but I wouldn’t put her in the same category as Laurette Taylor.

“I knew Laurette quite well. Three times she called me up when she was drinking, and twice, she made me cut my weekend in the country to come back into the city. I’d phone her back and all she could say was muum-muum-muum, and I thought, oh my God, again? But once I got there, she would snap out of it completely.”

One of the abiding legends of the theater is the breakout performance of Marlon Brando (a year before he played Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire) in the Maxwell Anderson play Truckline Cafe, which ran only 13 times before closing in 1946. Few people saw it, but Tonio did. “I went with Lotte Lenya to the opening of Truckline Cafe, and there I met Marlon Brando for the first time. He was incredible in that play. We went backstage afterward. Brando’s mother was with him backstage.” At the time, Brando was just shy of his 22nd birthday. “Much later on, when I talked with Brando about that play, he said he had worked with Stella Adler on that part. He more or less gave all the compliments to her.” (Frances Tannehill and her husband, Alexander Clark, also saw Truckline Cafe. “Oh my God, he electrified the audience,” she recalled of Brando.)

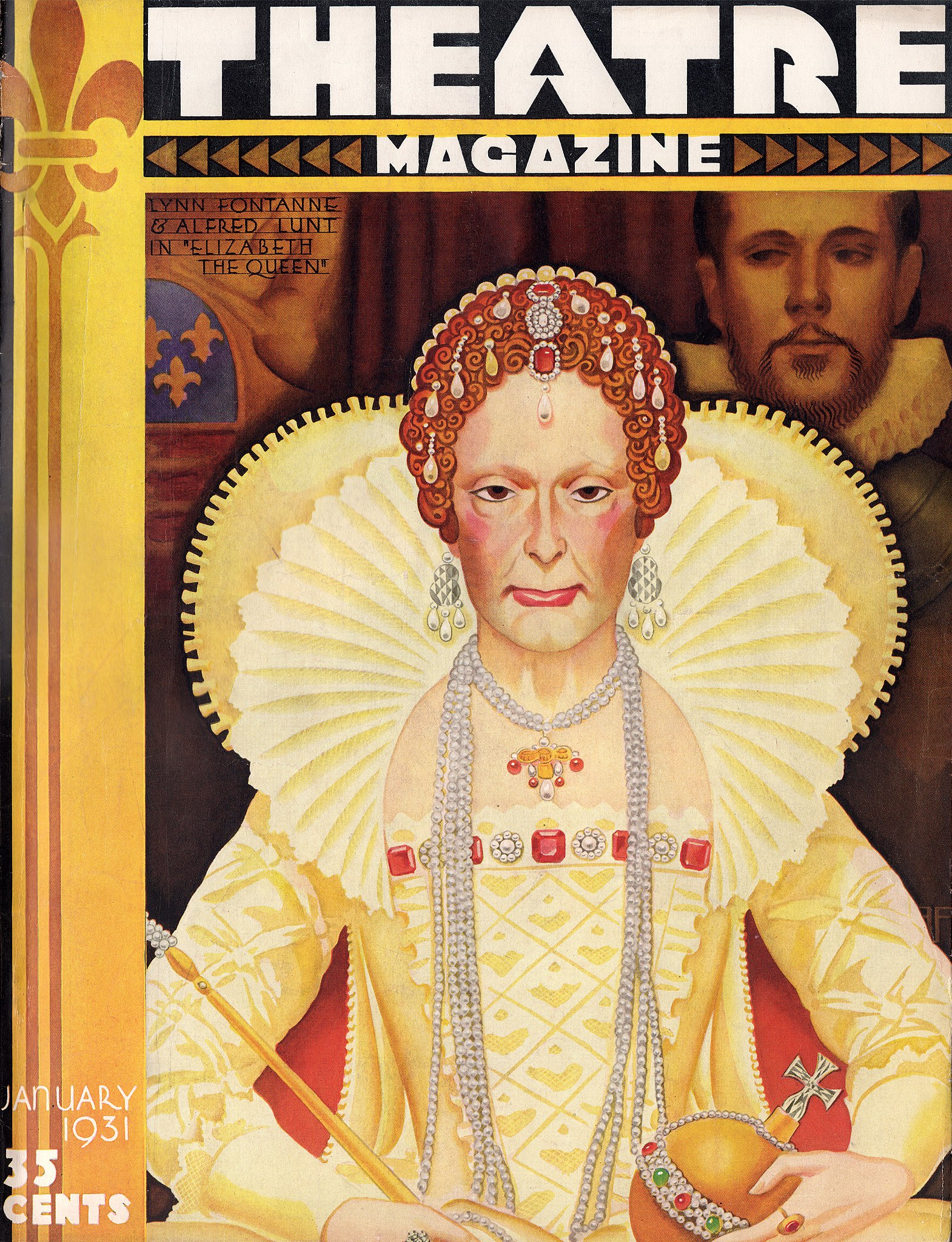

Front cover of the January 1931 issue of Theatre Magazine, featuring Lynn Fontanne and Alfred Lunt in Maxwell Anderson’s play Elizabeth the Queen (Theatre Magazine/Wikimedia Commons)

III

“The early 1950s is when the star system fell apart,” the actress Meg Mundy—a star herself in the 1948 Broadway production of Jean-Paul Sartre’s notoriously titled play The Respectful Prostitute—told me. “In the 1930s, there were road shows out for each thing on Broadway. The Lunts were famous for that—they’d hit New York after they’d played six months on tour. That’s one reason they were so good when they hit New York. In the early 1950s, at first no stage actor would go on TV. That’s how all us young kids got opportunities. Until a little later, no stage person would think of going on television.”

The technique of performing on the TV camera was alien to some of that theater era’s larger-than-life performers. “Alex Segal, who directed the U.S. Steel Hour on TV, cast Tallulah Bankhead as Hedda Gabler in 1954, toward the end of her career,” Mundy recalled. “God knows she had a shtick. In rehearsal he said he got her absolutely straight, no shtick whatsoever. Came the countdown to live air of 4-3-2-1, and she became frightened, and the whole performance was shtick, because she knew she could get by with that.” Recalled Tonio, “I worked with Gertrude Lawrence on what was her first live television, on The Prudential Family Playhouse in 1950. She was very nervous. When they counted down, she said to me, ‘Now there’s no going back!’ But of course when the moment came and she was on, she was fine.” Lawrence died suddenly at 54 only two years later, in the middle of her Broadway run as Anna Leonowens in The King and I. One of her few straight dramatic roles in movies was Amanda Wingfield in the now little remembered 1950 film of The Glass Menagerie.

There are still great actors today, and Broadway still makes a profit, but rarely from plays that aren’t musicals. In the decades immediately following the retirement of the Lunts and Cornell, Uta Hagen, Marian Seldes, and Julie Harris were primarily identified as actresses of the theater, though they all occasionally appeared in movies and television. A few actors, like Christopher Plummer and Kevin Kline, were also known as theater specialists. Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy carried on the great married couple tradition late into the 20th century, but they never imitated the Lunts. Today fine actors primarily known from TV and movies, like George Clooney, Denzel Washington, and Jeff Daniels, put bodies in the seats, but they are not exclusive practitioners of the stage like the performers of olden times. Though a few actors are still primarily identified with the theater medium—Patti LuPone, Audra McDonald, Nathan Lane—there are no longer stars like the Lunts and Cornell who produced and sometimes directed their own vehicles. Movies that celebrate the glamour and uniqueness of the theater barely exist today: a rare exception like the 2014 film Birdman used the theater world more as an incidental backdrop than a central focus.

There were no Tony awards until 1947, but more notably, the Tony Awards were not televised until 1967. Now attention is mainly paid to the winners and which musical numbers are most impressive on TV, rather than on the actual plays and performances. A couple years ago, I attended a performance of the revival of Funny Girl. The actress starring in the lead role, Lea Michele, was replaced that night by her part-time alternate, a young, relatively unknown singer named Julie Benko. To my astonishment, when she made her first stage entrance, the audience gave her a thundering round of applause as if she were Lynn Fontanne. How could that be? Then I realized that Benko had already cultivated a social media fan base, which had brought many young people to the performance. Times change. In the 1940s, when rookie actors had a thin CV of previous credits, they would confabulate their bios in the Playbill in keeping with the “magic” of the theater. (Marlon Brando did this when he made his Broadway debut in I Remember Mama in 1944.) Today, even actors making their debuts list their website addresses in their Playbill bios.

The legitimate theater in New York is a thriving business but is no longer considered a crown jewel of American culture. Some 40 years ago, I was standing outdoors on a line at the Baronet & Coronet movie house on Third Avenue and East 59th Street (I no longer remember for which movie). While we were waiting, the actress Ruth Gordon emerged from the theater and walked by the line. A gentleman next to me started clapping enthusiastically and shouting, “Ruth Gordon!” and a few patrons joined in. Gordon acknowledged the claque with a twinkle in her eye, a self-deprecating grin, and a downward wave of her hand, and said with theatrical bravura, “Never mind me, hurry up inside to see the show!” Gordon had enjoyed some late fame for her role in the film Harold and Maude, but I sensed the claque knew her from the live theater. A scene like that could not happen today on the streets of New York. Nobody would know who someone like that was.

IV

Over the years, I have managed to catch several of Tonio Selwart’s film performances: the German ambassador to Woodrow Wilson’s White House in the 1944 biopic Wilson; Nazi roles in two 1943 films, Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die and Lewis Milestone’s The North Star; a lesser nobleman in The Barefoot Contessa (1954) with Humphrey Bogart and Ava Gardner. Only a few years ago did I finally manage to see him in Orson Welles’s last big film, The Other Side of the Wind, which was released in 2018, more than 40 years after most of it had been completed. Tonio played the important supporting role of the Baron, the personal manager of filmmaker Jake Hannaford (played by John Huston). The role is allegedly modeled on Welles’s long ago Mercury Theatre producing partner, John Houseman.

By the time I met him in 1998, Tonio had already outlived most of the cast of The Other Side of the Wind, all of whom were much younger than he: Cameron Mitchell, John Huston, Norman Foster, Lili Palmer, Edmond O’Brien, Paul Stewart. Susan Strasberg, also in the film, passed away about six months after I met Tonio.

Tonio had seen Orson Welles in his first Broadway role, as Tybalt in Katharine Cornell’s production of Romeo and Juliet in the 1934–35 season. Welles was then 19 years old. In my second visit to him, Tonio proudly pulled out a handwritten letter from Welles. I read it out loud into my tape recorder:

April 21, 1975. Dearest Tonio, I am sure you will be very happy to be liberated from this palm-fringed prison camp to be free to fly back to your home and friends. But for me, this is a sad occasion. I find myself wishing that your part in this film would go on forever, and that we could meet night after night doing more and more new scenes. Indeed, it’s with the greatest difficulty that I resist the temptation to write just one more page of dialogue for “the baron.” You have contributed an extraordinary performance to our picture. I will be forever grateful to you for that, as I rejoice in our friendship, Yours ever, Orson.

As a boy taken to the theater in the 1960s, I caught a few last gasps of the grand era, though I was too young to appreciate most of what I saw (for example, John Gielgud’s all-star production of Richard Burton’s Hamlet—although I remember spotting Adlai Stevenson in the audience during intermission.) A tad later, in 1970, I sat in the center of the first row of the orchestra to watch Jimmy Stewart and Helen Hayes in a revival of Harvey at the ANTA Playhouse (now renamed the August Wilson Theatre). It was Hayes’s final appearance on Broadway, playing the little old lady role she was typecast in during her later years. Her real brilliance as a dramatic actress in her prime can be seen in her few Pre-Code films of the early 1930s. As I sat overawed by his physical proximity, Stewart totally suspended my disbelief: He had me dead convinced that he saw a large rabbit, invisible to others, next to him.

I still have the playbill.